Crooner: A Love Song Lyric Generator

The problem of de novo text generation has direct application in fields such as social media, content generation, direct response marketing, predictive text, machine translation, and customer service automation. To explore this space, I built love-song lyric generator trained on a real-world dataset, returning entirely new song lyrics based on a user generated seed text. Data was collected from Spotify and Genius lyrics and modeled with a LSTM Neural Network to create entirely new songs.

This may also serve as a foundational underpinning for complete song or voice generation models which may be used across a variety of Enterprise applications.

Problem Statement

This project aims to build a word-level love-song lyric generator trained on a real-world dataset made up of existing tracks and returning entirely new song lyrics based on a user generated seed text.

The problem of de novo text generation has direct application in fields such as social media content generation, direct response marketing, predictive text generation, or text-based customer service correspondence. This may also serve as a foundational underpinning for complete song or voice generation models which may be used across a variety of Enterprise applications.

Executive Summary

Exploring word-level models based on an LSTM neural network architecture, my model was able to achieve 86.9% training accuracy and generate convincing lyrics that preserve basic song structure.

Here is an example song generated with the seed ‘eyes are for lovers’:

The dataset was collected by querying the Spotify API (source) for Spotify Curated playlist track lists from the Romance genre and then scraping the Genius lyric database (source) to build a corpus of 1781 tracks and 12334 unique words.

After cleaning the data, training and optimizing a LSTM model and generating sample lyrics, the model was deployed in a console application as well as proof of concept Flask app.

Background

Predictive text generation models have been deployed by companies such as Google with wide adoption. Current production models are commonly built upon neural network architectures such as Convolutional Neural Nets (CNNs) or more recently Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) using character-level predictions.

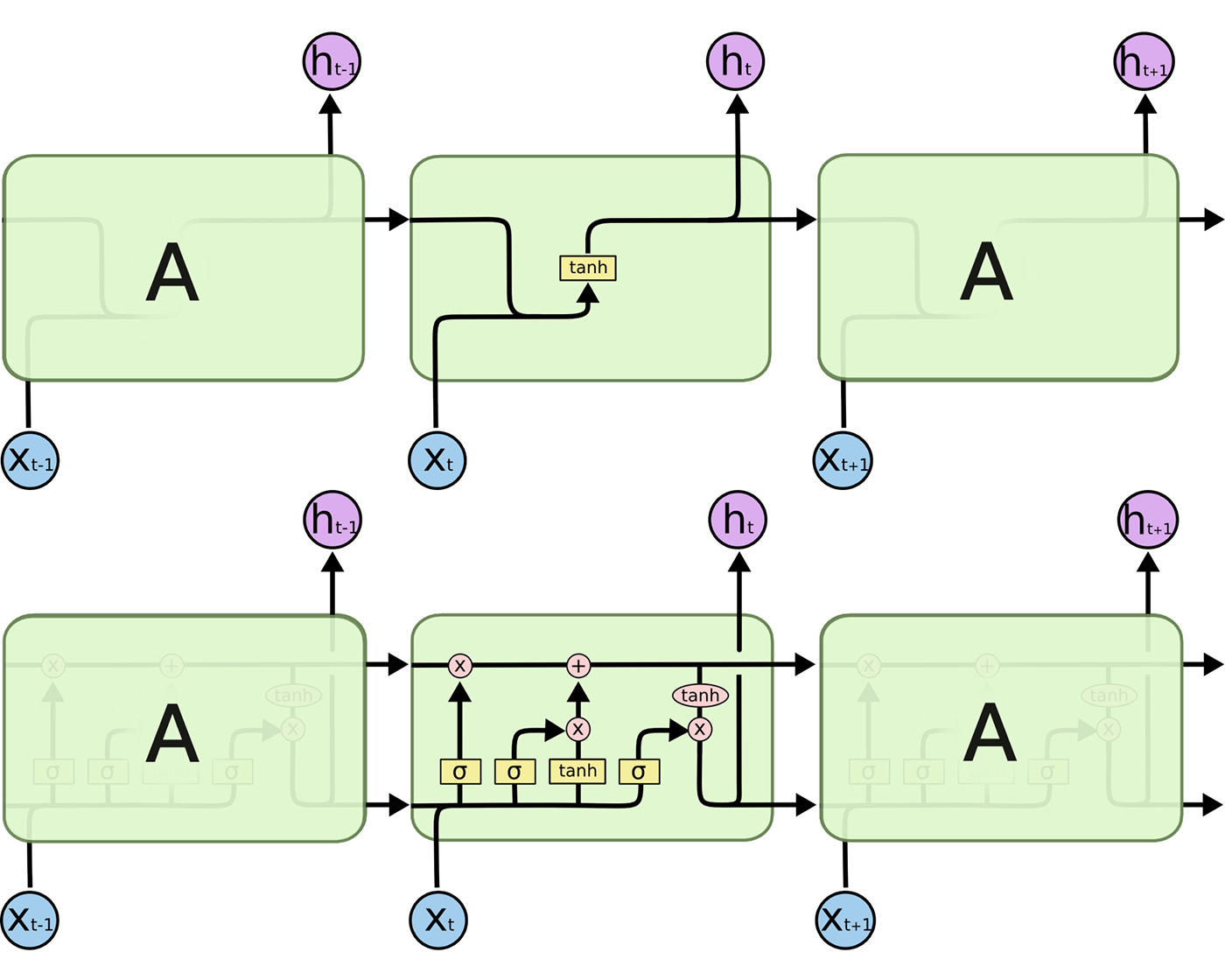

While RNNs have been shown to produce strong results for more shallow networks and shorter texts, their performance tends to drop off with deeper architectures. This is due to a property dubbed the vanishing gradient problem, which describes an issue with downstream layers losing the ability to tune the weights of earlier layers. To address this issue, Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) networks allow samples to pass directly through to downstream layers, thereby preserving a direct path for tuning via forward and back-propagation. (source)

An unrolled RNN (top) vs LSTM (bottom) (source)

An unrolled RNN (top) vs LSTM (bottom) (source)

A single LSTM cell has 3 states: a forget gate, a memory gate, and a sigmoid output layer. The first layer determines what information is kept from previous states, the next layer determines what new information will be added to the cell, and the final layer determines what information will be passed to the next LSTM cell. In this way, LSTM cells are able to avoid the problem of the vanishing gradient.

Leveraging the deep learning libraries of Keras running on a Tensorflow backend, a dataset of 1781 songs was split into 567142 training sequences and passed through the model. The songs were collected from the Romance category of Spotify Curated playlists. Each playlist is between 15-100 tracks and is professionally selected by Spotify Staff. Lyrics were scraped from Genius, one of the largest lyric databases populated by moderated user annotated lyrics. Once collected, the data was pushed to a SQL database for possible use as a backend server.

Song lyrics were cleaned and split into individual words for each track before processing and being fed into the model as tokenized word-level sequence sets. Predictions based on these input sets were validated against the ground truth next word in the track and the models were scored based on accuracy.

Data Dictionary

SQL Tables:

track_table:

| Feature | SQL Type | Data Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| track_id | VARCHAR / PRIMARY KEY | string | Unique track ID assigned by Spotify and used to trace back to song metadata throughout this project. |

| playlist_id | VARCHAR | string | Unique playlist ID assigned by Spotify and used to group tracks by playlist. |

| track_name | VARCHAR | string | Name of the Track. |

| artist_name | VARCHAR | string | Name of the Artist. |

| album_name | VARCHAR | string | Name of the Album. |

| playlist_name | VARCHAR | string | Name of the Spotify playlist. |

| playlist_owner | VARCHAR | string | Name of the playlist creator (Spotify). |

| lyrics | JSON | string | Lyrics queried from Genius (http://genius.com) |

lyric_table:

| Feature | SQL Type | Data Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| track_id | VARCHAR / PRIMARY KEY | string | Unique track ID assigned by Spotify and used to trace back to song metadata throughout this project. |

| rep_ratio | FLOAT | float | Ratio of unique words to total words in the track |

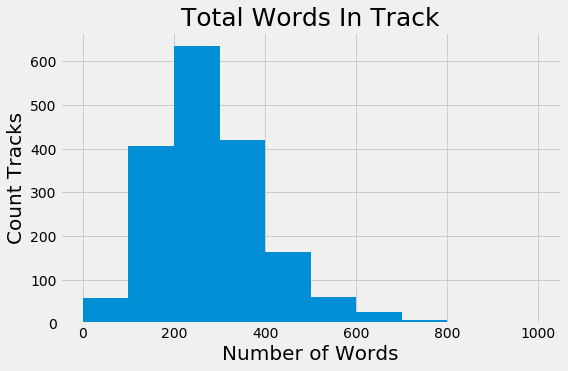

| total_words_track | INT | int | Word count for the track |

| unique_words_track | INT | int | Unique word count for the track |

| mean_len_words_track | FLOAT | float | Mean word length for the track |

| total_lines_track | INT | int | Line count for the track |

| unique_lines_track | INT | int | Unique line count for the track |

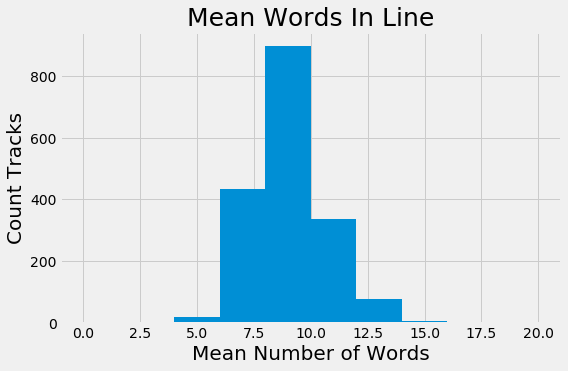

| mean_words_line | FLOAT | float | Mean word count per line in the track |

| mean_unique_words_line | FLOAT | float | Mean unique word count per line in the track |

Findings

Creating a python-based word-level text generator, I decided to implement a sliding window sequence to feed data into the model. This means that an input sequence of m words will be used to generate an output sequence of n words. Sequencing the data in this way has the benefit of providing a ground truth feature that can be used to score model accuracy during training.

Based on song structure findings during EDA, I decided on an input sequence of four words, an output sequence of one word, and a 250 word song length. This corresponds to an average of 9.1 words/line and 282.6 words/track seen in the dataset. I also chose to keep ‘\n’ characters in an effort to preserve song structure.

Based on track length, I decided to build my model with an embedding layer followed by a first LSTM layer of 300 nodes, corresponding to roughly 1 node per word in the track. This feeds into a second LSTM layer with 150 nodes, followed by a Dense layer with 100 nodes and finally an output layer with the same shape as the training corpus.

The best results were produced when using a model trained over 300 epochs with batches of 5000 input sequences and untrained word word vectors with 3000 dimensions. The optimization function was the ADAM optimizer and the loss function was categorical cross-entropy.

The model architecture was as follows:

- Keras Embedding (3000)

- LSTM (300, return_sequences=True)

- LSTM (150)

- Dense (100, ReLu)

- Dense (vocab_size, softmax)

The Keras embedding layer is randomly initialized and fit alongside the model during training. Since I started with a vocabulary of 12334 unique words it seemed reasonable to begin with reducing the input dimensionality down to a 3000 feature dense representation. I also explored the use of pre-trained word vectors from the GloVe Common Crawl 42B dataset for comparison (source).

Lyrics produced from a model fit with pre-trained word vectors from the GloVe 42B dataset were more likely to repeat or fall into loops, requiring a larger variance coefficient during lyric generation to avoid repetition. This may indicated a need for more training epochs or a deeper overall model architecture. Since the embeddings were not a parameter being fit by the model, it is also possible that allowing the model to update embedding weights would also lead to better results. Line structure was also markedly less robust, often being choppy and 4-6 words compared to the longer lines of other models.

To inject a tunable amount of variance in the model predictions, predicted probabilities for the next word were scaled and then randomly sampled from a distribution. This technique, adopted from the Keras LSTM example framework, prevents predictions from falling into a loop of high likelihood word patterns or into lyrics that the model was initially trained on (source).

This framework produced 250 word lyric sets that showed minimal repetition, maintained human readability, and preserved an output structure that could pass as real-world lyrics.

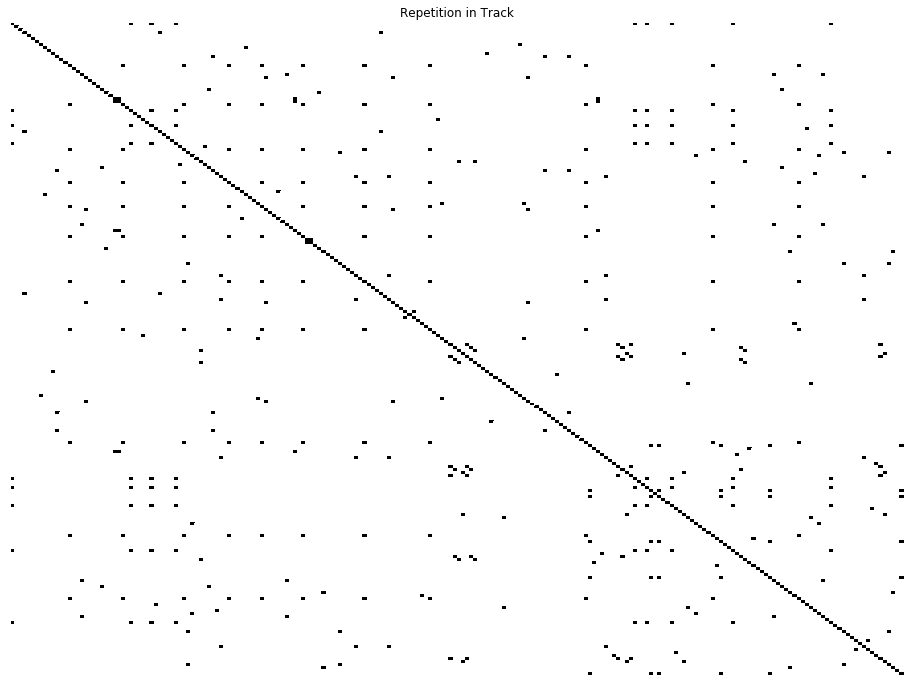

Reviewing song structure as a repetition grid, here is the output for the model generated track from above:

Model-generated song repetition grid without pre-trained embeddings

Model-generated song repetition grid without pre-trained embeddings

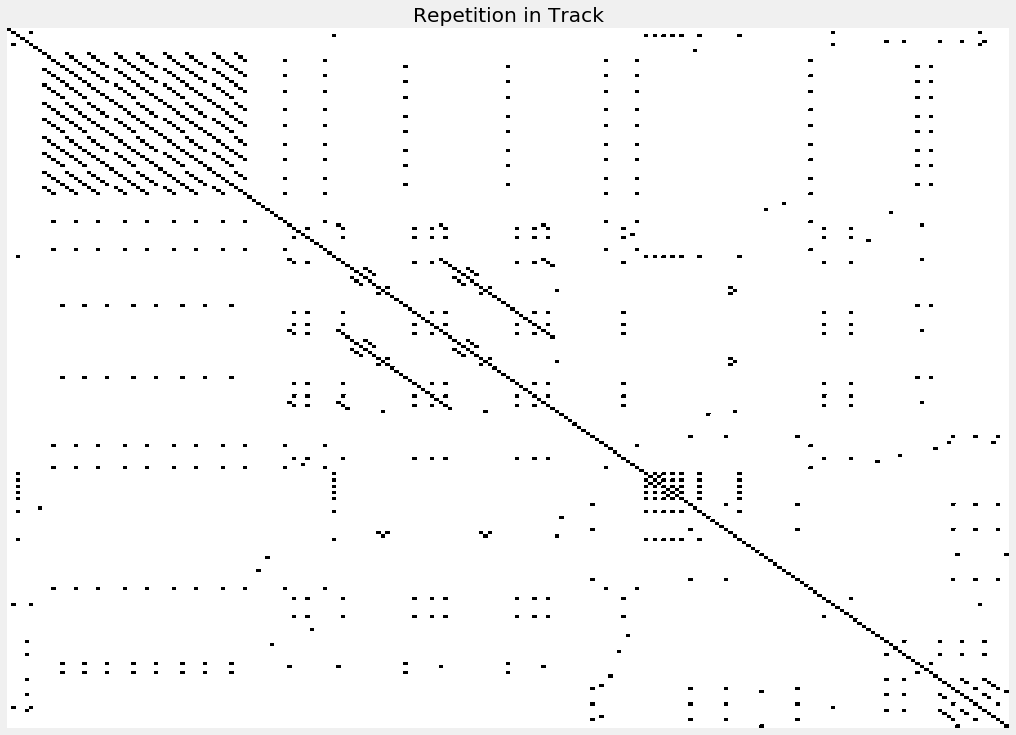

Model-generated song repetition grid with pre-trained embeddings

Model-generated song repetition grid with pre-trained embeddings

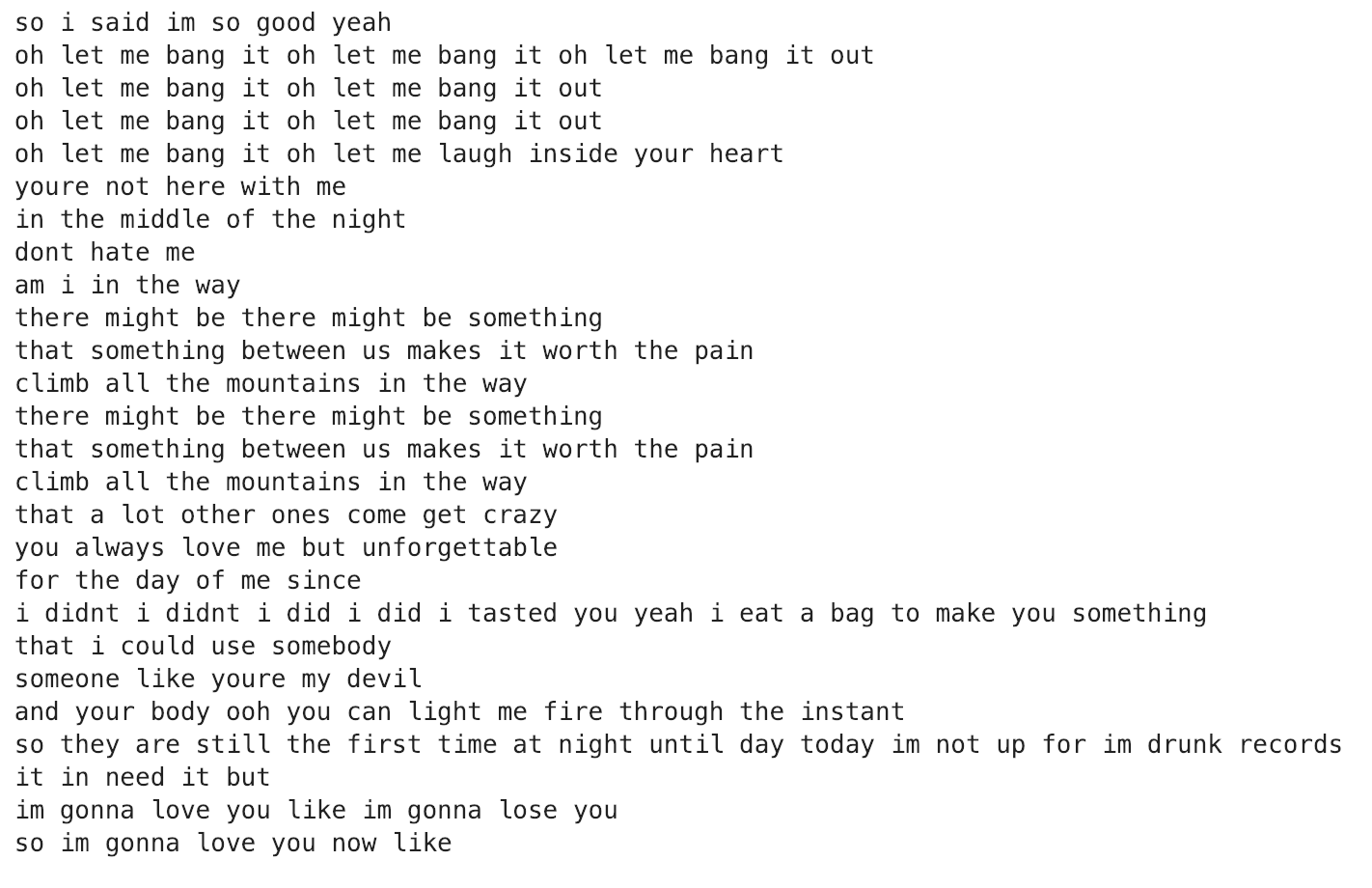

Lyrics generated from the seed ‘always be there love’

Lyrics generated from the seed ‘always be there love’

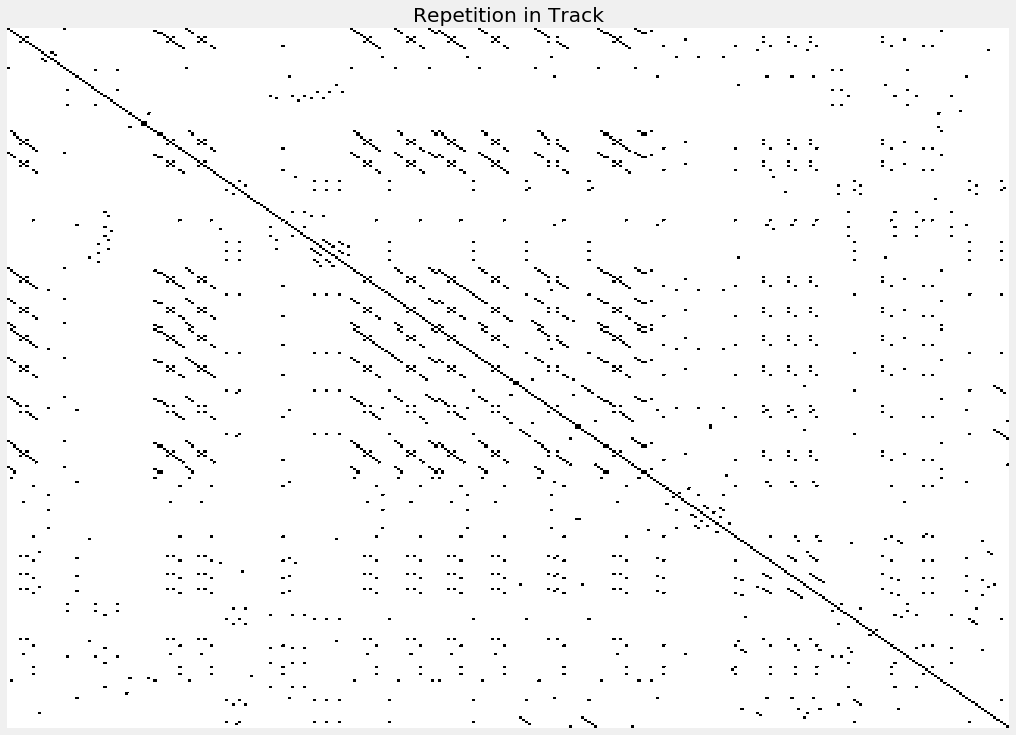

In this grid, the vertical and horizontal axis represent each word in the track. If a word is repeated, the cell is filled, otherwise it is left white. This can be compared to a real track below. Note that the song below has about 30% higher word repetition (~ 0.64, average for the dataset compared to 0.39 above). It is possible that as the model becomes better optimized these structural components will become more well-defined.

Real song repetition grid

Real song repetition grid

Lyrics for When Somebody Loves You Back, Teddy Pendergrass (source)

Lyrics for When Somebody Loves You Back, Teddy Pendergrass (source)

Business Recommendations

Based on my findings, it’s clear that LSTM models provide a solid architecture for language processing and text generation. This model is robust enough to produce entertaining results that can be deployed in a consumer level product with minimal additional front-end development.

This work provides a foundation for further exploration of word- and document-level language processing frameworks which can be applied to use-cases such as translation, marketing / copywriting, document summarization, image captioning, and other areas where automated speech and text may be beneficial.

In the context of personalized, targeted marketing where brand voice and authenticity are paramount, a model such as this one may be able to provide basic copy that requires minimal human-in-the-loop feedback to become a market-ready document that adheres to pre-established and longstanding brand guidelines.

Next steps

This model would benefit from a more exhaustive optimization of both architecture and hyperparameter tuning. To accomplish this will require scaling up compute.

One tool that I would be interested in exploring is the Adanet adaptive architecture package that can dynamically test the addition of layers and nodes to create better predictions. I would have also liked to have explored pre-trained word vectors with longer training runs as I’m confident that a better semantic understanding of the data would result in more humanistic predictions.

I would also like to build out the model with a more consumer-facing interface alongside the lyric repetition grid and interactive versions of other song structure plots produced during EDA.

A natural extension of this project would be training on a larger dataset that is grouped by genre to see how well the model can mimic not only syntax, but also sentiment according to well conserved song structures.

Another interesting idea would be training the model on company websites, press releases, and other public-facing documents to see how well the model can adopt brand voice.

Conclusion

It is clear this model has great potential for language processing and text generation. For a word-level model to produce these results on a relatively small dataset is frankly quite remarkable. As an exploratory project seeking to demonstrate the potential of LSTM architectures for generating human-readable text, this is a tremendous starting point. Consumer and enterprise-level use-cases for this functionality are broad and there’s no doubt that machine-generated language processing will only become more prevalent in the coming years.

Full project repo is available on GitHub

I'm a Data Scientist living in Santa Monica, CA. Driven by curiosity, I'm eager to apply ML and Data Science techniques to create scalable, robust solutions to complex problems.